Dear friends,

Whether you’re speeding or sailing or shambling toward the solstice, I hope this message finds you warm and well.

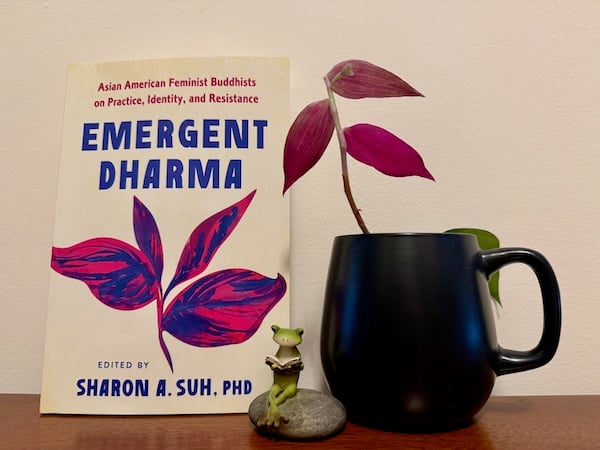

Winter has been serving up some seriously cold temperatures here in Southeast Michigan. In response to a screenshot from my weather app, a dear friend in California texted back: Thought that was Celsius?! Nope, I clarified, three degrees Fahrenheit, -16ºC. The perfect weather for reading Emergent Dharma with rapt attention while wrapped in an electrical blanket.

Emergent Dharma: Asian American Feminist Buddhists on Practice, Identity, and Resistance came out this past Tuesday. I recently heard a live performance of “The Twelve Days of Christmas” by Béla Fleck and the Flecktones (Fleck on banjo, Victor Wooten on bass, Roy Wooten on Drumitar/percussion, Jeff Coffin on sax) that culminated with Tuvan throat singing from the Alash Ensemble (Bady-Dorzhu Ondar, Ayan-ool Sam, Ayan Shirizhik). In the spirit of that fabulously zany rendition—every verse featured a different key (E-flat through D) and a different time signature (1/4 through 12/4)—here’s a riff on the dozen parts of Emergent Dharma (preface/intro + 10 body chapters + conclusion):

1) Preface + Introduction (Sharon Suh)

Counter to the prevailing notion that Asian American Buddhists simply adhere to their familiar religious rituals and beliefs, the narratives featured here reflect a more complicated picture of disavowal, yearning, ingratitude, and transformation with and through Buddhism. (p1)

—and delight and fun and joy!

2) My Mother Remains: An Immigrant Daughter’s Buddhist Reckoning with Filial Debt (Chenxing Han)

When it comes to a relationship as intense as the one between mother and child, “the flip side to such love and attachment might very well be ambivalence, guilt, submerged hostility.” (p31)

Rendering a fraught personal relationship into the public pages of this essay was a painful and profound process for me. Deep bows of gratitude to the Roots and Refuge sangha for opening the possibility of a phone call longer than 26 seconds; to the many people whose writing and translations shaped this essay (Trent Walker, Grace M. Cho, Maxine Hong Kingston, James Baldwin, Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, pseudonymous Redditors, Bhikkhu Bodhi, Billy Collins, Putsata Reang, Grégory Kourilsky, Reiko Ohnuma, erin Khuê Ninh, Erik W. Davis, Thích Nhất Hạnh, Bhikkhu Sujato, Tsering Wangmo Dhompa); and, of course, deepest bows of all to Dad—and Mom.

3) Infinite Light, Infinite Life (Funie Hsu/Chhî)

Looking back, I wonder if for A+ Po, Guan Yin represented a liberating possibility of existing beyond the material limitations of her life—and death. Perhaps the Bodhisattva was a pathway for her to realize that even though we were a struggling, working-class, immigrant family, she could still live her life in the abundance provided by her Buddhist values. (p47)

From my fellow May We Gather co-organizer Funie Hsu/Chhî, a multigenerational, interspecies, talk-story sutra full of bodhisattvas whose names I want to chant: A+ Po, A-Kong, A+ Tai, Aaron, Aiko, Kheh-Khì, Mr. Babie with his dhāraṇī-meows.

4) Grave Remembrance: Sustaining Connection and Caregiving Across Generations (Jane Iwamura)

After they both had passed, I looked after my parents in a different, but no less significant way. I assure them that they are loved and not forgotten and that they are still very much a part of our lives. I bring their grandchildren to come visit. We are not simply caretakers of the grave, but caregivers of the spirit. (p67)

This care-filled piece reminds me of the (re)creations and (re)orientations in Jane Iwamura’s 2003 article “Altared States: Exploring the Legacy of Japanese American Butsudan Practice.” From a pioneer in the field of Asian American lived religion, an honoring of the things we simply do, as part of the great chain of being.

5) Creating Desire Paths: On Being a “Bad Buddhist Auntie” (Mihiri Tillakaratne)

I’ll never be an “appropriate” Sri Lankan American Buddhist: I’m unmarried and childfree by choice; I’m loud, I curse, I take up space (metaphorically, physically, and conversationally), and I’m fat. Worst of all, I’m totally content with it! (p73)

Mihiri Tillakaratne offers up a delicious model of “doing diaspora” as a Bad Auntie whose politics of care blazes liberatory new paths. I first met Mihiri years ago—after she filmed I Take Refuge, before she co-founded Bodhi Leaves: The Asian American Buddhist Monthly at Lion’s Roar. In her forthright exchanges with the abbot of her temple, we are reminded that Auntiehood is capacious enough to censure your community’s nationalistic dogmas in one breath and feel pride for your community’s support of local Black Lives Matter protestors in the next.

6) Threading the Invisible Flower Garland: Stories of Asian (North) American Buddhist Women I Have Known (Mushim Patricia Ikeda)

“Did you hear what Grandma was muttering when she lit incense in the corner of the house and bowed?” I said. “Beats me. It sound liked namdabs, namdabs, namdabs,” my brother said. We agreed that we had no idea what she was doing or why. (p94)

In this eight-flowered lei of redolent memory and startling stories, Mushim Patricia Ikeda introduces us to a bevy of Asian diasporic Buddhists from Hawai‘i to Arizona to Ohio to Virginia to Toronto. There are family members like her Nembutsu-chanting grandma and spiritual kin like the 보살님 Polsalnim at Korean Buddhist temples, and then there’s Mushim, refusing to play the part of “invisible” or “visible threat,” living into her Dharma name forty years and counting.

7) Critical Affinity: A Scholar-Practitioner’s Memoir of Lived Buddhism (Nalika Gajaweera)

[F]or many lay Buddhists, giving blood (léh dan deema) also serves as a means of cultivating and transferring merit to the departed (pin anumodana). For my husband and me, it was an extension of our reciprocal responsibilities to our late parents; a familial duty and an act of care intimately tied to our Buddhist upbringing. (p107)

What does it mean to be scholar-practitioner and transnational Asian diasporic lay Buddhist? Nalika Gajaweera reckons with what it means to give blood and spill blood in the name of religion, how her spiritual inheritance has embraced and evaded Buddhist modernism, and why the weight of “cultural baggage” shifts from one context (Sinhalese Buddhist hegemony) to another (white convert dominance).

8) Art for Catharsis (or an Unborn Child): Transforming Trauma, Pain, and Loss into Healing Rituals (Naomi Kasumi)

Every full moon night, I have a conversation with Shion to keep him up to date on my life. I feel a profound spiritual connection with this invisible being. Many years after my abortion, I spontaneously wondered about the meaning of my unborn child’s name. (p121)

5,140 eggshells, each one painstakingly emptied by artist Naomi Kasumi, whose art-making practice is ritual and apology and memorial and 作務 samu (the daily physical tasks that maintain the temple) for a beloved 水子 mizuko named 紫苑 Shion.

9) Talk-Story from the Trenches: Asian American Buddhist Feminists in America (Tâm Thâm Tịnh and Thanda Aung)

Growing up, I was exposed to yummy vegetarian food in Buddhist ceremonies and fatalistic and superstitious Buddhism. The latter was not appealing to me, especially in its justification of restrictive gender roles. (TTT, p139)

In the Disney+ series American Born Chinese, Michelle Yeoh plays the Chinese Goddess of Compassion. Wise, compassionate, and humorous, she takes multiple forms. (TA, p151)

How do we practice peace when the world is marred by violence? Two pseudonymous Southeast Asian aunties tell it as it is on immigration (from Việt Nam and Burma), family, trauma, academia, and healing.

10) Being with the Body in a Body (Syd Yang)

Was I good enough to bow to Her? Was I Asian enough? My body hovered in that space between knowing and not knowing, lost within a pernicious interrogation of my “enoughness” until that moment when my shame convinced me to walk away, the untaken bow still vibrating in my limbs. (pp163–164)

Gazing up at Guanyin at Taroko National Park in Taiwan, Syd Yang confronts an androgynous, shape-shifting bodhisattva while grappling with their own struggles to find ease in a trans masculine, nonbinary body. A Buddhist in recovery traces their journey to body acceptance; embodied beings of all genders rejoice.

11) Asian American Feminist Buddhist Rage, Trauma, and Self-Love (Sharon Suh)

I don’t want to unleash hell on some unsuspecting innocent person out in public. I fantasize more about mustering up the entitlement and fearless privilege of no longer remaining silent about all the microaggressive violence meted out on smaller playing fields like the workplace, the grocery store, or city streets. And this is why Ali Wong’s unhinged character Amy Lau in the Netflix series Beef left such a delicious taste in my mouth. (p182)

Spoken like a true Asian American feminist killjoy Buddhist vegan. Kudos to Sharon Suh, editor and visionary and sangha-maker behind Emergent Dharma!

12) Conclusion (Sharon Suh)

“As Asian American feminist Buddhists, can we love ourselves as fiercely as we love others?”

Nuff said.

Til the next quarter moon,

~Chenxing

PS: On today’s photo: I didn’t register the resonance with the Emergent Dharma book cover when I adopted this friend at a plant swap a few months ago. The bud is a new development! May small wonders unfurl before our notice, even on the bleakest of days 🌬️🌱