Dear friends,

Biking to yoga in the early mornings after last Monday’s full moon (happy Mid-Autumn Festival! 🥮), I’ve been gazing up at the clear dark sky to see a waning lunar reminder to write to all of you.

To continue a thread from September’s newsletter: After my talk on “The Karma of Friendship: A Buddhist Approach to Writing & Spiritual Care” at the University of Lynchburg, an international student from Afghanistan asked the final question. You’re the first Buddhist I’ve ever met, she said. What is Buddhism’s view on life? Are we here to enjoy? Or does each of us have an appointed mission?

Q&A is my favorite part of book talks. Specifically, Q. (Which is also my favorite food texture, but I digress.) I usually feel my responses fail to match the magnitude of the question. The resulting sense of inadequacy is, in many ways, a gift, insofar as it plants a seed of lingering curiosity. Mulling over this Afghan student’s question about what constitutes a good life—pleasure? purpose?—I keep returning to something Dr. Nancy Lin, who teaches at the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Berkeley, California, once said to me in conversation: There are as many ways to be Buddhist as there are Buddhists in the world.

I’m drawn to the generosity and generativity of this perspective. It makes me want to meet—and learn from—more members of the Buddhist family tree. Really, the human family tree, in all our divisions and commonalities. Over the past two decades, Buddhism has suffused my life as tea remakes water, a fragrance and taste intensifying over time. As I asked the audience of my U of L talk: What flavor is your tea? What friendships are you steeping in? How are you a friend to others? Most importantly, how are you a friend to yourself?

Prof. Lin was teaching the Bodhicaryāvatāra that term, which inspired me to pick up my copy of Śāntideva’s eight-century text, translated by Kate Crosby and Andrew Skilton. The verses are full of beauty and surprise from the very beginning. I have a soft spot for the second verse:

Nothing new will be said here, nor have I any skill in composition. Therefore I do not imagine that I can benefit others. I have done this to perfume my own mind.

Which might be the ultimate humblebrag! But, taken sincerely, this verse is a vivid encapsulation of writing as a form of play wherein dualities of pleasure and purpose, self and other, begin to dissolve.

While these newsletters are no Bodhicaryāvatāra, my hope for them is no different than Śāntideva’s third verse (though I’d replace “he” with “they” to include all potential readers):

While doing this, the surge of my inspiration to cultivate what is skilful increases. Moreover, should another, of the very same humours as me, also look at this, then he too may benefit from it.

Or, as Jiryu Mark Rutschman-Byler puts it, thirteen centuries later, in an article about training an AI bot (!) on the teachings of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi (!!):

My only hope, as a teacher, is that the assembly might listen charitably with the whole and sincere heart of their own embodied practice: “I vow to taste the truth of the Tathagata’s words.” From my side, the parallel prayer is something like this: “Despite my words, may you all somehow hear the true dharma!”

How can we as fleeting, embodied human beings hear and taste (and see and smell and touch) the lasting peace and stable joy of the true dharma? I was asking myself this on October 2nd, the anniversary of my beloved college roommate’s passing. Amy’s death was the impetus for my second book, which weaves in snippets of her writing:

There is nothing missing in the moments it takes for me to turn over each heirloom tomato at the farmer’s market, not just because I’m looking for one to buy, but also because each is unique and lumpy, and bitten, and unexpected. There’s nothing missing in admiring the quirky college student making circles on her bike with a giant sunflower hanging out of her backpack.

That morning, I texted a photo of the sunflower-filled Princeton Farmers Market to a childhood friend of Amy’s. Ellen wrote back, “If I squint hard enough I can see Amy back there in the market delighting at the flowers,” then texted a video of Amy in the hospital exclaiming, “I love Tay-Tay! She’s amazing!” We marveled that it was the eve of Taylor Swift’s twelfth album drop. I’d even opened the U of L talk with a Swifty song on karma.

It was the first time since Amy’s death nine years ago that I spent this anniversary of mourning with close friends. Listening to the Buddhist in Our Backyard had made Andy and Julia and their two kids spiritual kin; they’d recently moved from Massachusetts to New Jersey. On that balmy autumn afternoon, we visited the local Sri Lankan temple, got groceries for dinner, picked up the kids from daycare and first grade, played badminton in the backyard, drummed on giant gourds in the school garden, disappointed the chickens by opening their feed bin and failing to take further action, then ate and sang and danced at Andy and Julia’s home into the evening.

How essential spiritual friendship is on days of grief. How much more so in these times of community-destroying political turmoil.

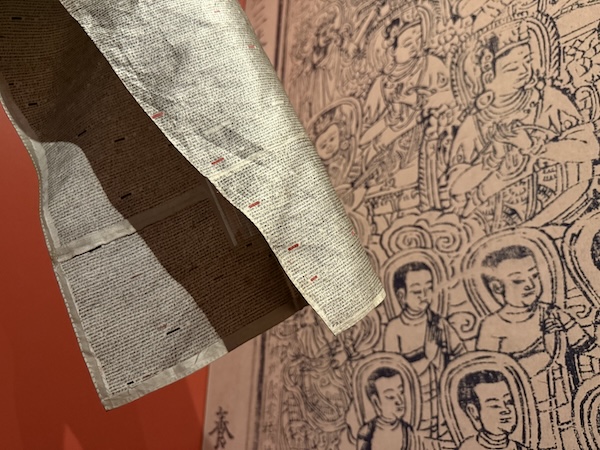

Between the farmer’s market and the temple visit, I stopped by Forms & Function: The Splendors of Global Book Making. Curated by Martin Heijdra, the exhibit runs until December 7 at the Princeton University Library. A comprehensive catalogue describes all seventy-three items on display, though the full splendor of the exhibit is best appreciated in person. Some of my favorite “books” in the exhibit: Egyptian papyrus, Islamic textual amulets, Buddhist palm leaf manuscripts, Ethiopian healing scrolls, a Protestant hymnal, in Ningbo dialect, a Cantonese poetry collection written by Chinese immigrants and published in San Francisco.

The photo at the top of today’s letter shows a 19th-century silk garment covered in more than half a million tiny Chinese characters. The background is an enlargement of an image from a 13th-century Chinese Buddhist woodprint, but the garment isn’t for religious purposes: Those 500,000+ characters are comprised of 700+ essays for the civil service exam. (The ultimate crib sheet, if you had a magnifying glass and a giraffe’s neck.)

Imagine draping this word-drenched cloak over your torso. What if the text were a transcript of your thoughts? What it the characters recorded every sentence out of your mouth? How would it feel to literally wear our emotions on our sleeves? If karma, for Buddhists, refers to intentional actions of body, speech, and mind, would such a garment not embody the sacred power of words—mentally generated, verbally expressed, physically written down?

Books, like Buddhists, take many forms in many places over many periods of time. The forms echo and mirror and influence each other, like the jewels of Indra’s net. After the Afghan student’s question in the Snidow Chapel at the University of Lynchburg, a professor of religious studies from nearby Randolph College pointed to the wall behind me. Had I noticed my backdrop? I had not. In lieu of stained glass: a latticework with large gem-like shapes where the diagonal lines met.

Indra’s net had been there the whole time. I needed a friend to realize it.

Til the next quarter moon,

~Chenxing